Notes and observations from Winning the Third World: Sino-American Rivalry During the Cold War, by Gregg Brazinsky. University of North Carolina Press, 2017, and Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World, by Jeremy Friedman. University of North Carolina Press, 2015. Continue reading “Notebook: Winning the Third World + Shadow Cold War”

Flipping through the Nikkei Asian Review

Until publication ceased in 2009, the Far Eastern Economic Review reigned as the Economist of the Pacific. For its devoted fans, no other English language publication better covered the sweep of the region’s politics, business, and culture. In the years since, other publications have stepped up their Asian coverage, mostly focused on China’s rise. That country’s state media in particular has increased the volume of information it produces, slanted but nonetheless useful. New media and newsletters have simultaneously sought to make sense of the cacophony while also adding to it.

Until publication ceased in 2009, the Far Eastern Economic Review reigned as the Economist of the Pacific. For its devoted fans, no other English language publication better covered the sweep of the region’s politics, business, and culture. In the years since, other publications have stepped up their Asian coverage, mostly focused on China’s rise. That country’s state media in particular has increased the volume of information it produces, slanted but nonetheless useful. New media and newsletters have simultaneously sought to make sense of the cacophony while also adding to it.

Japan’s English-language Nikkei Asian Review has quietly worked to change that since it began publication in 2013. It professes to be a “global publication with a uniquely Asian perspective,” leveraging the 24 bureaux and 1300 reporters of Japan’s leading business newspaper. In 2015, its parent acquired the Financial Times. Despite its prominent sister publications, the magazine has attracted a modest audience of 25 thousand print subscribers and 2 million unique monthly page views. Are the rest of us missing out?

The overseas Chinese agenda

Next month, China will host its national equivalent of the Olympic Games. This year, for the first time overseas Chinese nationals will also be able to participate. More telling is the inclusion of foreign athletes of Chinese ancestry. The initiative is one of many attempts, some subtle and others not, by Beijing to signal control of its citizens abroad and effectively nationalize ethnic Chinese regardless of citizenship in service of Beijing. How aggressively China pursues this strategy will impact the country’s relationships with nations that are home to significant populations of both overseas Chinese nationals and ethnic Chinese. Already, some nations are sounding alarms not heard since the end of the Cold War. For their part, overseas Chinese worry how the influence campaign may put them at risk in both countries.

Are the tea leaves still good?

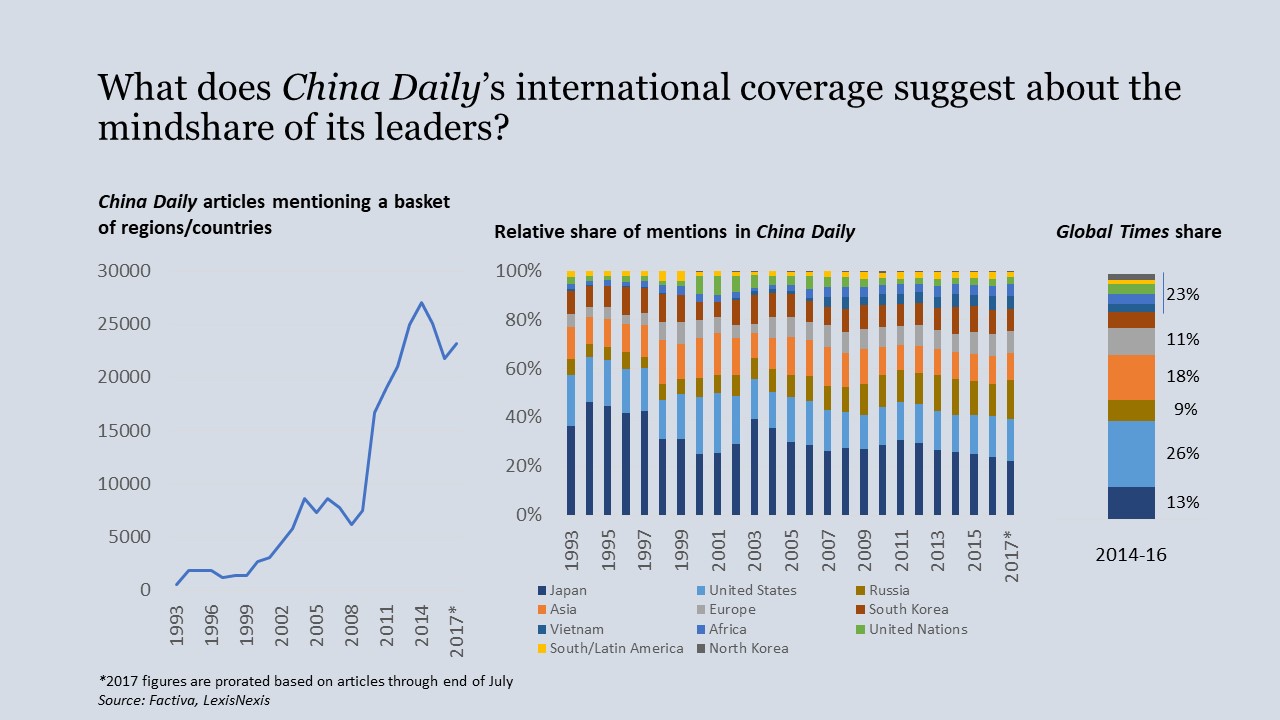

Reading the tea leaves in old-school Kremlin- or Sinology has often meant paying close attention to newspapers – what is said and what isn’t, who is mentioned and who isn’t. The approach may still have its uses for understanding Chinese foreign affairs.

Reading the tea leaves in old-school Kremlin- or Sinology has often meant paying close attention to newspapers – what is said and what isn’t, who is mentioned and who isn’t. The approach may still have its uses for understanding Chinese foreign affairs.

An analysis of recent years of China Daily’s coverage may suggest important insights about how China sees the world. Over the past decade, articles mentioning a basket of regions or specific countries has exploded. This reflects China’s growing global presence and its deepening, if unbalanced international expertise.

Tellingly, Japan, the United States, and Russia, account for a majority of countries/regions mentioned. Africa and Latin America, where Chinese involvement attracts significant scrutiny, are almost non-existent. Global Times, which tends to be more nationalist, devotes a significantly higher share of its articles to the United States and Asia in general.

As the primary government-controlled newspaper meant for foreign consumption, this indicates more than just the paper’s targeted audience. It also suggests the “mindshare” that each country and region commands among the Chinese leadership. Japan remains top of mind.

What does Asian rap mean?

It’s been a breakout year of sorts for Asian and Asian-American rappers alike. New York City rapper and television personality, Awkwafina, née Nora Lum, is co-starring in the all-female Ocean’s Eight remake alongside marquee names such as Sandra Bullock and Cate Blanchett. In the spring, a group of Chinese rappers dropped a diss track against America’s antimissile system in South Korea, which, despite the laughter it triggered, was a win for the propaganda apparatus simply by being noticed. And earlier this week, Korean-American rapper Jay Park signed with Roc Nation, the label founded by Jay-Z and home to artists including Rihanna. “This is a win for Korea,” he wrote on Instagram. “This is a win for Asian Americans. This is a win for the overlooked and underappreciated.”

God with Chinese characteristics

Review of The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao, by Ian Johnson. Pantheon, 2017.

There are limits to New Journalism. At its best, by rendering the author as a fully formed presence, it makes difficult or distant subject matter more approachable. Often, it is essentially an extended illuminating anecdote. But it can also, instead of rendering a larger phenomenon understandable, compound the reader’s disorientation. In these instances, the curiosity of the author can come at the expense of the analysis deserved by the reader. Such is the tension with Ian Johnson’s The Souls of China, an exploration of the return of religion after Mao. Continue reading “God with Chinese characteristics”

What to read on your first trip to China

As we enter high summer, another cohort of students are preparing to spend their summer or fall semester in China. In the past few years a flurry of books have been published that provide nuanced and up-to-date perspectives on the country for general readers. Here are those CBR most recommends for the best possible sweep of how China’s history, politics, economics, and society interact.

Wealth and Power by Orville Schell and John Delury provides the historical context that has shaped modern China through eleven profiles of leaders and thinkers including Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Readers will find in the nationalistic pride, humiliation, and conflicted feelings about the West captured in these pages a clear path to Xi Jinping’s “China Dream.”

Dark horizon

Review of Everything Under the Heavens: How the Past Helps Shape China’s Push for Global Power, by Howard French. Knopf, 2017.

National myths and obsessions have long and consequential half-lives. In the 1590s, Japan’s feudal ruler, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, envisioned his country’s conquest of all of Asia. Its fateful decision to embrace modernity fueled Japanese economic and military power and reinforced its sense of racial superiority. On the other side of the world, as Yale’s Timothy Snyder writes in Black Earth (2015), Hitler conjured a dark ideology mixing distorted history, a radical interpretation of Darwinism, eugenics, and age-old anti-Semitism. These visions enabled the destructive reality of World War II and its enduring consequences.

It is now China that is succumbing to the dangers of national mythmaking, according to Howard French’s new book, Everything Under the Heavens: How the Past Helps Shape China’s Push for Global Power. In a breathless opening chapter, French, a former bureau chief for the New York Times, abandons the cool observation that marked his last book on China’s growing influence in Africa, to warn that the risk of conflict in Asia is high and potentially unavoidable.

Fear and faith in Beijing

The first election in which I was old enough to vote, I found myself in Shanghai. When the absentee ballot arrived, I passed it flippantly to my language tutor, telling her to vote. “It may be the only time you get to do it,” I teased. I remember her fascination with my state’s ballot initiatives and her delight in my being one small vote in favor of gay marriage, in-state tuition for undocumented migrants – which I explained by use of China’s hukou system as metaphor – and against gambling.

Throughout the campaign, I remember being grateful for the objective remove – away from the negative advertisements and talk shows and with only the certain words of the New York Times. When Obama won reelection in 2012, I felt pride in my country, relief that his first victory had not been a fluke, that this was truth of America’s hopefulness and confidence in the future. This time was different.

Meritocracy with Chinese characteristics

Review of The China Model: Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy, by Daniel Bell. Princeton University Press, 2015.

As natural as it may seem for the more than three billion people in countries where it has taken root, in the grand sweep of history the idea that ordinary people should choose their own leaders is still revolutionary. Nonetheless, a kind of ideological hegemony has taken hold wherever democracy flourishes. Defenders habitually quote Churchill’s quip that democracy is “the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried.” Others have heralded democracy as “the end of history”; in other words, the form of government that is most morally legitimate, stable, and likely to secure peace and prosperity.

China, according to Daniel Bell’s book, The China Model¸ ought to challenge this hypothesis. Bell, a professor and political theorist at Tsinghua University in Beijing, makes the case for what he terms “political meritocracy,” the selection of leaders “in accordance with ability and virtue” (6) and not by the ballot. Political meritocracy, he argues, is a distinct form of government separate from a despotic authoritarianism in which power is held by the threat of force, not merit. The book is as thought-provoking as it is frustrating, earning The China Model a place on as many “best of” lists last year as it did strident rebuttals.