Next month, China will host its national equivalent of the Olympic Games. This year, for the first time overseas Chinese nationals will also be able to participate. More telling is the inclusion of foreign athletes of Chinese ancestry. The initiative is one of many attempts, some subtle and others not, by Beijing to signal control of its citizens abroad and effectively nationalize ethnic Chinese regardless of citizenship in service of Beijing. How aggressively China pursues this strategy will impact the country’s relationships with nations that are home to significant populations of both overseas Chinese nationals and ethnic Chinese. Already, some nations are sounding alarms not heard since the end of the Cold War. For their part, overseas Chinese worry how the influence campaign may put them at risk in both countries.

The Chinese diaspora has existed since the late Qing dynasty era, but has grown rapidly to an estimated 60 million today. Countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, and the United States each have several million. In other countries, the proportions are more telling, such as Singapore, where nearly three-quarters of the population is ethnic Chinese. In Australia, where ethnic Chinese account for somewhat over 5% of the population, the community has grown six-fold since 1986. In regions such as Africa, noticeable Chinese presence has only been felt in the past decade. The history, size, and nuances of each country’s diasporas vary widely, but no longer is the story primarily that of Chinese pushed abroad by hardship or persecution. Instead, today’s migrants are seeking to capitalize on China’s progress, whether that comes in the form of a Western education or assets.

Diasporas have the potential to bring important cultural and economic benefits to receiving and sending countries alike. It is this kind of “win-win” opportunity that China’s government prefers to emphasize when speaking to external audiences. The same week that China announced it would open its National Games to overseas and ethnic Chinese, its Prime Minister, Li Keqiang, met with a delegation of overseas Chinese businesspeople. Li encouraged the group to “lend talents and resources” by investing in China. He also asked them to support the country’s far-reaching, but ill-defined Belt and Road international development strategy, an effort to link the global economy more closely to China. (For all its benefits, the continued reliance on overseas Chinese risks becoming a crutch that limits the country’s ability to truly understand and engage with the world.)

In between declarations of friendship, cultural exchange, and economic opportunity, Li also stressed that overseas Chinese do more to “promote” and “safeguard” the one-China principle, which Beijing interprets to mean that Taiwan is a part of China. It is this political activation that worries some observers, pointing to concerns that span improper political influence, intimidation of overseas Chinese, and espionage.

Australia’s Fairfax Media reported earlier this summer that millions in donations to political parties were made by Chinese businesspeople connected with Beijing. The paper described Australian intelligence officials’ belief that “Australia was the target of an opaque foreign interference campaign by China on a larger scale than that being carried out by any other nation.” Efforts are now underway to ban foreign donations in Australian politics in response.

Beyond politics, Western university campuses have also been subject to the influence campaign. Chinese nationals who publicly criticize their home country, such as what one University of Maryland senior from Kunming did this spring, are swiftly denounced. The country’s prickly nationalism means that this needs little official encouragement. More telling are the coordinated efforts by Chinese embassies through Chinese Students and Scholars Associations to protest invitations to figures such as the Dalai Lama or other student activities deemed contrary to the country’s core interests.

The extraterritorial mindset extends elsewhere. Chinese-language newspapers serving immigrant communities from Australia to Canada have been pressured or acquired by entities with mainland interests. Undeclared Chinese agents have entered the United States, which does not have an extradition treaty with the country, to pressure fugitives to return home. Uighurs, the minority Muslim ethnic group, have been forced to return to the mainland. Several former Chinese nationals holding foreign passports have been renditioned from Hong Kong and Thailand back to the mainland, prompting one Western diplomat to tell the Financial Times that the “deliberate blurring of ethnicity and nationality” Beijing is undertaking was “deeply troubling.”

Beijing has also sought to exploit its diaspora for espionage purposes. A report by the nonpartisan Chinese-American organization Committee of 100 has found that since 2009, the number of ethnic Chinese charged with economic espionage crimes have tripled. These actions heighten the insecurity of Chinese-American communities, who are simultaneously vulnerable to foreign intimidation and believe themselves to be targets of discrimination by their adopted countries. The Committee of 100 report was meant to protest what it believes to be unfair scrutiny.

Writing in May, state councilor Yang Jiechi, notes that “overseas Chinese work’s connection with the country’s domestic and foreign affairs has strengthened.” He stresses that overseas efforts must “contain separatist forces” pursuing Taiwanese, Xinjiang, or Tibetan independence. To that end, he reports that more than 200 anti-independence groups and sixteen peaceful unification conferences have been held. This number does not appear to have been previously reported, but there are no further indications of where these groups are operating.

The present emphasis on overseas Chinese could be considered the fourth such wave in China’s history. In the first, overseas Chinese were influential in the fall of the Qing dynasty. As early as the 1920s, Mao envisioned that overseas Chinese would play a role in spreading communism throughout Asia, efforts which persisted throughout the Cold War. And as China opened up under Deng Xiaoping, the country made special appeals to overseas Chinese, particularly in the sciences.

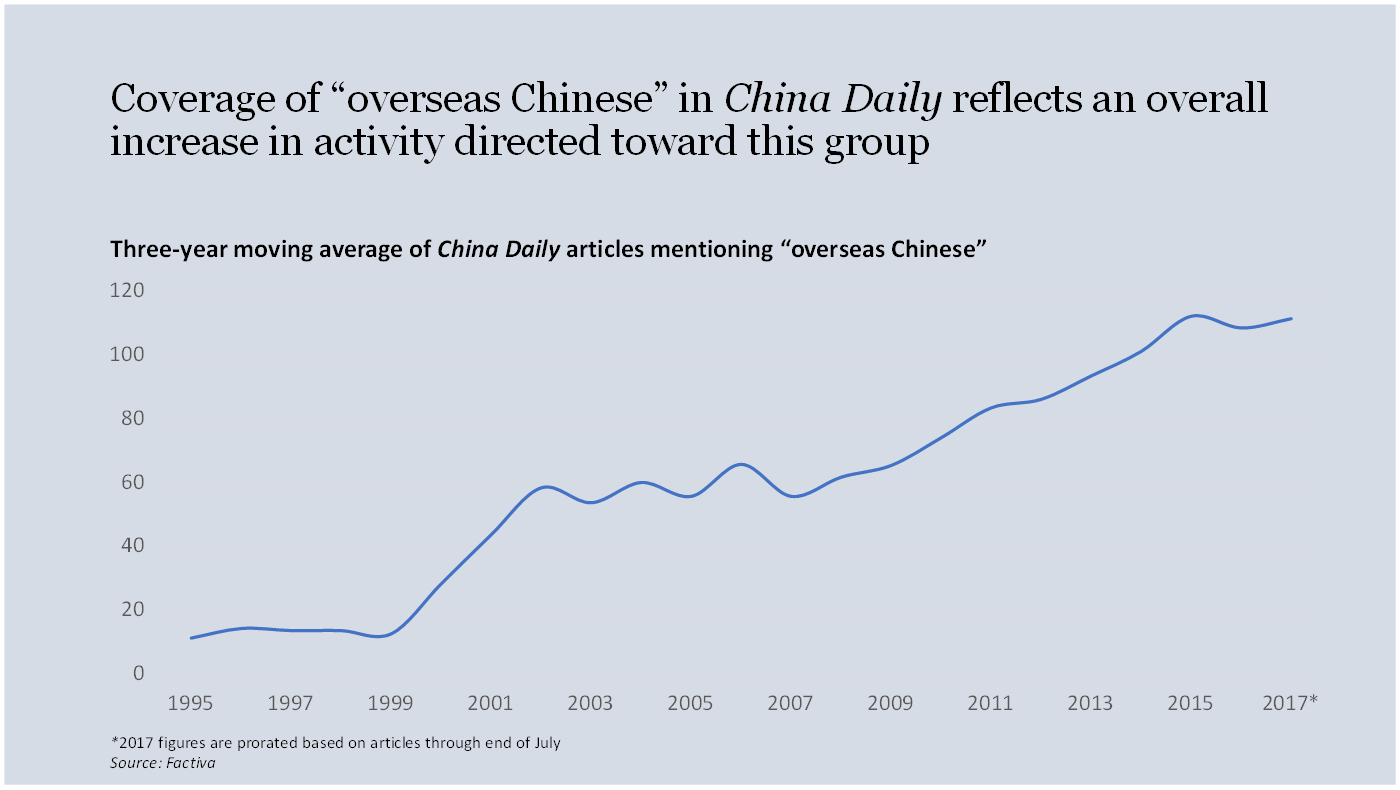

Heightened attention to overseas Chinese in the present era coincides with increasingly racialized rhetoric on the mainland as President Xi Jinping’s “China Dream” effectively calls for the “rejuvenation of the Chinese race.” In Xi’s next term, observers will continue to watch how the growing presence of Chinese citizens and economic interests abroad affects Beijing’s “non-interference” policy.

On the surface, these trends manifest themselves as signs of greater strength. More significantly, they reveal that whatever new capabilities for influence China’s wealth has afforded it, deep insecurities remain. Indeed, the aggressiveness of the response may mean that those insecurities are becoming more difficult to contain.