Twitter, at its best, offers immediate, direct, and transparent conversation on the most important issues of the day. But it can also be a driver of polarization and misinformation. To its credit, global China-watchers maintain one of the Twitter communities that most consistently realizes the platform’s positive potential.

But who are the most influential China-focused tweeters? CBR is introducing an index to find out, weighting equally public and elite influence. The former is measured by the number of followers an account has and the latter by an account’s betweenness centrality, a measure used in network analysis that quantifies how connected an individual is to other prominent accounts. Three rankings were produced for individual accounts predominantly tweeting in English or Chinese and institutional accounts in any language.

Jeremy Goldkorn, editor of supChina, ranks as the most influential individual English-language account focused on China, followed by New York Times reporter Michael Forsythe, and Bill Bishop, editor of the Sinocism newsletter. Ai Weiwei has the most influential Chinese-language individual account, followed by commentator Michael Anti, and Yunchao Wen, an internet activist. People’s Daily is the most influential institutional account, followed by China.org.cn and the New York Times Chinese account.

That journalists generally outperform academics or practitioners is unsurprising given that the platform has become an extension of their work. But the findings may also underscore a need for academics and practitioners to play a more active role in the world’s most visible town square instead of focusing on just journal papers and communiques.

In recent months, Chinese officials have begun joining Twitter, a service which is blocked in the mainland, and which the country continues to punish citizens for using. Measured by the controversy some officials’ tweets have prompted, they are fitting right in with the platform’s tendency to raucousness. In July, former US national security advisor Susan Rice tweeted that a Chinese diplomat was a “racist disgrace” after the Chinese official inartfully invoked US race relations to deflect criticism of Beijing’s treatment of the Muslim Uyghur minority group. Evidence has also emerged of China’s use of Twitter to sow disinformation. Amid the Hong Kong protests, Twitter and other platforms acted to suspend hundreds of state-linked fake accounts.

How these results were produced

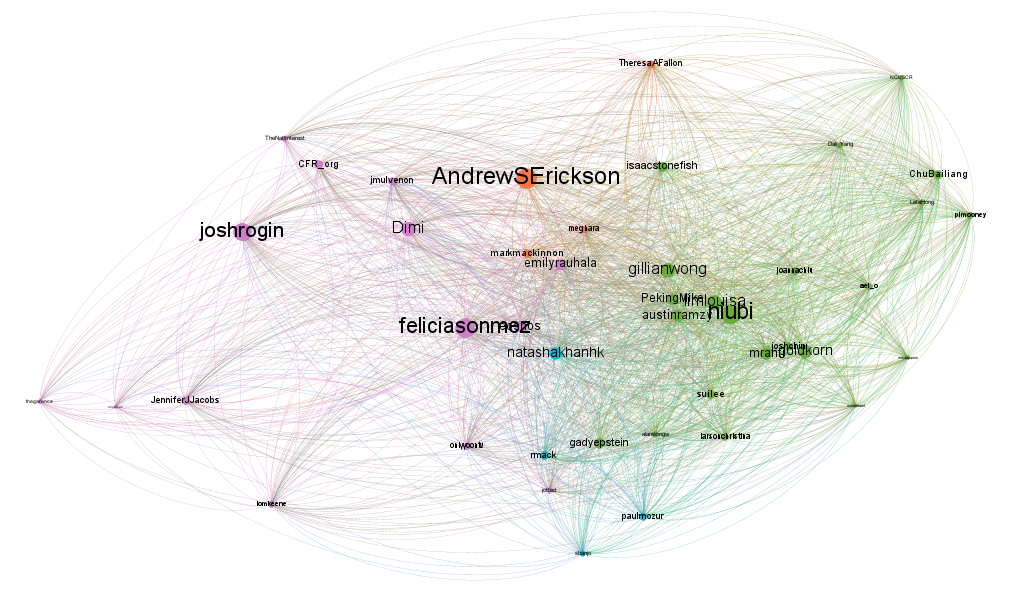

In early September, CBR downloaded Twitter metadata, which the company makes available to those who submit a brief application and structure their queries via one of several programming languages. The analysis was performed using the Twitter API, R, and the Gephi network graphing software.

To create a universe of relevant accounts, CBR started with the prominent commentator Bill Bishop and extended out one degree of separation to the people followed by the people he follows. This approach doesn’t affect the number of followers but would impact the betweenness centrality score. Accordingly, the index capped any account with a centrality score within the 90th percentile of their respective category.

A pre-release version of the index also considered the total volume of tweets. This was not included in the final version for several reasons, chiefly so as not to penalize newer accounts and because users differ on how extensively they use their accounts to tweet about other topics, which could not be readily accounted for.

The 2,871 accounts followed by Bishop – excluding an additional 300 accounts not captured, mostly because they were private – spirals to more than one million unique followed accounts at one degree of separation. The number of accounts under analysis was sharply pruned to those followed by at least 100 of the accounts Bishop followed. That results in a more manageable set of 4,892 accounts, but a still formidable 800 thousand recorded relationships between them.

The ranking does not consider accounts which pass this screen but do not predominantly tweet about China. Using an institutional and individual account as an example, this would exclude the official account of the Council on Foreign Relations or Washington Post columnist, Josh Rogin, which both otherwise rank highly. The index also removes individuals who may have formerly tweeted predominantly on topics related to China but have since moved on to other roles, such as Felicia Sonmez, who was formerly a Wall Street Journal and AFP reporter based in Beijing but now covers US politics. This definition is inevitably subjective: the decision was made to include Edward Wong, a former China correspondent for the Times who now covers diplomacy, because China remains an active focus of his account.

CBR welcomes your feedback about the China Twitter Influence index at [email protected].