No one believes that China’s economy is sustainable in present form – not even its government. Beijing and most external experts agree that continued growth is possible, just not from the combination of cheap labor, exports, and infrastructure investment it historically depended on. In its place, the economy must transition to higher value-added goods and services. But for China’s workers to become more productive, they must be better educated. A host of worrying studies, many led by Stanford’s Rural Education Action Program, suggest that China’s young people are not being educated broadly enough to make that transition.

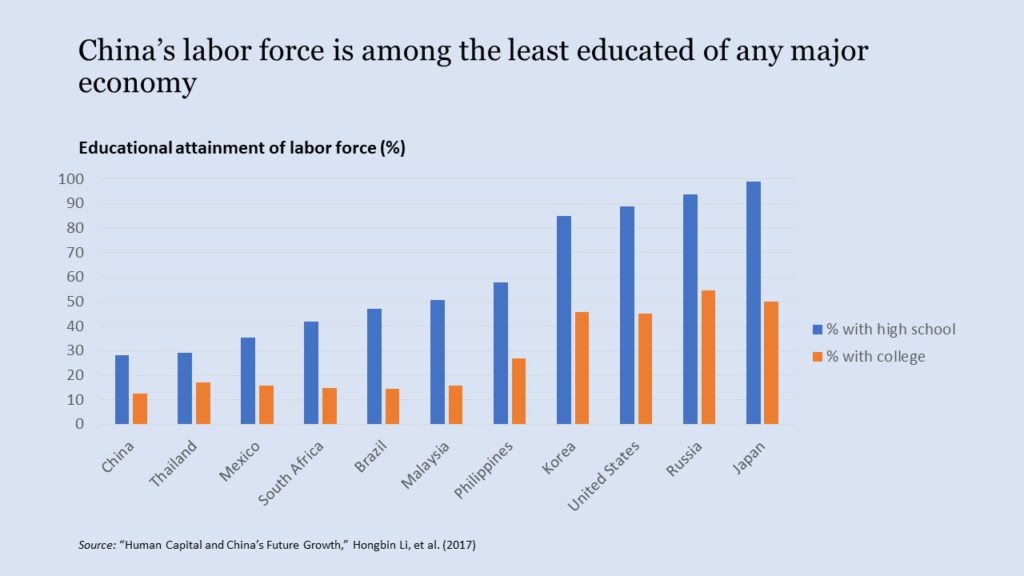

Only 28 percent of China’s labor force has a high school education, among the worst of any major developing country. Many of the older generations suffered because of extreme poverty and the Cultural Revolution’s upheaval. Yet, younger workers fare little better with a high school completion rate of just 36 percent. The stalled growth and inequality that this portends threatens to shake the world.

Most outsiders are only familiar with China’s education success stories. Today, even those vaguely familiar with the country know the tremendous academic pressure its children face. There is also no shortage of parents choosing to opt-out of the gaokao exams and pay tremendous sums so that their children can go not just to Western colleges, but high and even elementary schools. The country’s students in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Guangzhou score well beyond Americans in math and science and have high school attainment rates of 90 percent. But China is a big country and a highly uneven one. In stark contrast, provinces like Guangxi have upper secondary attainment rates of 26 percent.

China’s educational failure is driven by its urban-rural inequality. Rural schools have fewer resources and qualified teachers. For poor families, the costs of school and the temptation of work persist as barriers. So too is the crippling pervasiveness of malnutrition: some estimates suggest as many as 60% of China’s elementary school children “have at least one health or nutrition problem that can seriously affect early cognitive skill development.” The urban-rural divide is compounded by the country’s internal migration (hukou) system which ties migrants’ benefits to their province of origin. As parents head east in search of work, they are faced with the decision of whether or not to bring their children. If they leave them behind along with 60 million others, their children will remain in poor schools and often suffer psychologically. If they add their children to the 35.8 million migrant children, most will end up with only marginally better educations in migrant schools.

The link between education and growth

The most important driver of economic growth is a nation’s people. China’s economic liftoff was made possible by a growing working population, their move to industrialized cities, and the opening to more productive private business. The country’s urbanization rate was just 18% forty years ago; today it is 56 percent. The share of workers in the vastly more productive private sector rocketed eightfold since 1989 to 80% today. This dividend is now all but exhausted. China’s workforce has begun to shrink and by 2030, the population of those older than 65 will almost double to 243 million.

As countries move into middle-income status, their economies often stagnate. Progress for middle-income countries is “believed to be in large part dependent on human capital accumulation,” a group led by the Asia Development Bank’s Niny Khor writes. A separate group of Chinese and Stanford researchers found that, by 2014, a country’s average years of schooling explained 74% of the variation in a country’s income.

China, Niny Khor’s team believes, is in crisis. “No country with levels of education even twice as high as those of China has ever progressed from middle-income to high-income status,” they write. Under what Li terms an “aggressive” scenario, if China is able to increase college and high school enrollment by 5 percent per year and 11 percent per year, by 2035 average years of schooling would have increased by 1.7 years. (China’s current 13th five-year plan calls for an increase of .6 years by 2020.) Based on Li’s figures, China would be able to sustainably grow at 3%.

Even as China’s educational foundation struggles, it has not neglected the universities that are needed for its transition to an innovative economy. In 2014, 7.2 million Chinese matriculated in higher education institutions, up from 2.2 million in 2000. Some 12.5% of Chinese now possess a college education. Like Deng Xiaoping’s invocation “to let some people get rich first,” the country is concentrating on a few universities. Only Peking (29th) and Tsinghua (35th) are in the Times Higher Education ranking’s world top 50; the next best is 153rd.

China may still be able to grow by focusing on the most technologically intensive sectors, but many workers would still be left behind, exacerbating already high levels of inequality and holding back the consumer economy. Already automation is affecting China’s workforce: manufacturing dynamo Foxconn, which makes the iPhone and other products, replaced 60,000 workers in a single factory. If estimates by consultancy PwC that 46% of the UK’s workers with a high school education or below would be at high risk of automation holds, 35% of China’s entire labor force would be at risk.

The implications of an inadequately educated workforce resonate far beyond the country’s economy. The legitimacy of the country’s one-party system is contingent upon the prosperity it has delivered and the promise of more. If that no longer holds, the government may yet manage to adapt by focusing on quality of life and deepening welfare. More likely, is that instability grows – or is masked by heightened repression. Internationally, a China that hobbles along may be tempted by neo-mercantilist policies while global growth overall slows.

Can the gap be closed?

China’s efforts to improve rural schools have focused on consolidation and teacher quality. National appropriations for education have jumped to above 4% of GDP in 2014 from 2.7% in 2005. The 30 trillion RMB in total spending in 2014 has grown three times above 2005 levels. Local governments responded to falling birth rates and migration to cities by consolidating three-quarters of rural schools. This could have been a potential boon as resources were more concentrated. Unfortunately, longer journeys mean that half of secondary students must board at significant cost to their families. While new funding and mandates for teaching training have been implemented, their results have been limited. A typical Chinese teacher’s salary is insufficient to attract the talented professionals China’s schools need.

China needs to do far more. It can better support migrant children and eliminate the hidden costs of education. Its national commitment to “universalize one to three years of pre-school” by 2020 could deliver significant gains. China can also foster a more egalitarian mindset by eliminating the zhongkao as a hurdle for admission to secondary school and leveraging its propaganda apparatus to make high school a national expectation.

Innovation and openness can also play a part. The NGO Teach for China has expanded from its roots in Yunnan to include Guangdong, Gansu, and Guangxi, but began turning away Western volunteers in 2015 in response to a more difficult political environment for NGOs. The program so far counts 1000 alumni, a third of what Teach for America produces each year. China’s most recent five-year plans have indicated an openness to foreign investment in pre-schools and childcare centers, but few details exist, and they will most likely be of little benefit to the poor. Last, the country must prepare its social safety net for the reality of far larger numbers of people who need help, perhaps indefinitely.

China’s inadequate education system is a national crisis that – unlike its environmental one – is all but hidden. (Indeed, some of the Stanford researchers believe the Ministry of Education’s estimates of upper secondary education are “overestimated.”) In the country’s development plans, education does not prominently feature, but is coupled more broadly under urban-rural inequality. China’s leaders have been obsequiously praised by outsiders for their willingness to make investments with payoffs decades into the future. But China has failed to make the most important investment of them all, in its people.