There is nothing that requires the event that defines a year to happen within it. So it was with this year when, in the waning days of 2019, a then-unknown virus began to spread rapidly from individuals who had frequented a wet market in Wuhan, China. Local officials, nearly two decades after SARS, defaulted to their usual approach to bad news: a cover-up. But, as citizens and leaders the world over would confront in manifold ways this year, a virus is impervious to political imperatives.

Soon, in part thanks to the heroic efforts of Li Wenliang, a doctor whom local police sought to silence and ultimately succumbed to the virus, the central government took notice, but waited to act, allowing the virus to further spread during the largest annual human migration that surrounds the Chinese New Year.

As reports from Wuhan grew more grave, the world looked on, many simultaneously doubting the statistics reported by Beijing and taking false comfort in the suggestion that human transmission was limited, guidance repeated unquestioningly by the World Health Organization. They saw China’s rush to build entirely new hospitals as emblematic of the failures of a development model that sees in every problem an engineering solution. They bristled at the sharply enforced lockdowns intended to slow the virus’s spread. They mistakenly saw the virus as a Chinese problem.

But China is vastly more connected to the rest of the world than it was when SARS broke out. Foreign executives, suddenly made aware that some critical component for which no ready alternative existed was fabricated in Wuhan, began to panic. But it is not just supply chains, but human connections that touch every corner of the globe. The virus exploited them.

In another 2020, free governments would have heeded the warnings of their scientists and begun to prepare for the virus’ inevitable arrival on their shores. Their citizens, trusting in their institutions and united in common cause with each other, would have begun to act decisively to prevent hundreds of thousands of deaths. In another 2020, popular anger at the CCP’s handling of the virus and subsequent economic fallout might have forced a chastened Xi Jinping to roll back his autocratic consolidation of power.

But this was not that 2020. While many nations, including China, succeeded in rallying their institutions and citizens to contain the virus, America, misled by Donald Trump, was chief among those which made a mockery of itself. Meanwhile, China made bold moves in nearly every domain. In one view, China acted boldly to assert its interests while the world was distracted; in another, recognizing that the virus eviscerated what little tailwinds remained of its destined incomplete rise, the country acted to seize as much as it could while it could.

Politics

China’s comparatively swift containment of the coronavirus relative to other nations mitigated initial political damage to the Party. In February, Dr. Li Wenliang’s death prompted widespread online protest under the guise of mourning; by August, Wuhan was host to a massive pool party.

Xi Jinping continued to consolidate his power, with a purge of the domestic security forces among the year’s most notable manifestations. Repression reigned, in scales ranging from outspoken individuals to an entire city and multiple ethnic groups. Among the individual targets of Beijing’s wrath were those who most directly challenged Xi Jinping. Xu Zhangrun, a Tsinghua professor who wrote a series of essays criticizing Xi Jinping, was briefly detained and lost both his job and pension. Ren Zhiqiang, an outspoken property magnate, was sentenced to 18 years in prison for various alleged improprieties after calling Xi Jinping a “clown.” Cai Xia, a teacher at the influential Central Party School, was expelled from the Communist Party (she had fled to America last year) after criticizing the Party as a “political zombie” which needed to be “jettisoned.”

In Hong Kong, Beijing delivered a reply as dramatic as last year’s protest movement: bypassing local authorities, the central government imposed a sweeping national security law which went into effect on the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover and effectively marked the end of the “one-country, two-systems” framework that was to grant the city relative autonomy through 2047. The chilling effect was immediate as groups dissolved and individuals scrambled to take down social media posts. Police moved to arrest and charge both prominent opposition leaders and unknown protesters alike, including Jimmy Lai, publisher of the adversarial Apple Daily newspaper. Activists, including Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow, were sentenced to months in prison on charges of unauthorized assembly. To enforce the new law, Beijing appointed Zheng Yanxiong to lead a national security office. Earlier in the year Beijing replaced the head of the central government’s liaison office; chief executive Carrie Lam and other establishment figures remained in their diminished roles. Citing the coronavirus, the government delayed elections originally scheduled for September. In November, all of the opposition Legislative Council members resigned in solidarity against Beijing’s maneuvering to oust some of their colleagues.

In Xinjiang, abuses against Uyghurs continued, with evidence of new detention facilities and forced use of birth control, sterilization, and abortion. Since 2017, two-thirds of mosques in the territory have been destroyed or damaged. During the American presidential campaign, Joe Biden denounced Beijing’s behavior in Xinjiang as “genocide.” President Trump signed the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, which permits sanctions against Chinese officials responsible for rights violations; former national security adviser John Bolton disclosed in his memoir that, in response to President Xi Jinping’s explanation of the need for detention camps, President Trump replied that it was “exactly the right thing to do.” In a fall work conference, Xi Jinping declared that “happiness” was on the rise in Xinjiang and that the party’s policies there were “completely correct.” Calls to boycott the 2022 Winter Olympics in China are expected to grow. Persecution of ethnic minorities also extended beyond Xinjiang. In Inner Mongolia, ethnic Mongolians, long considered China’s “model minority,” briefly protested a move to supplant minority language instruction with Mandarin. In Tibet, reports emerged of a mass labor program, a “targeted attack on traditional Tibetan livelihoods.”

In Taiwan, Tsai-Ing-wen was reelected as president. The United States advanced its relationship with Taipei on multiple dimensions, including the approval of billions in new weapons sales; the highest-level visits in decades by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar and Under Secretary of State Keith Krach; and the broaching of a trade agreement. Echoing Kennedy in Berlin, the head of the Czech Senate declared before Taiwan’s parliament, “I am Taiwanese.” In Macau, the tourism-driven economy was battered by the loss of mainland visitors due to the coronavirus. Lobsang Sangay, president of the Tibetan Central Administration, was the first political leader of Tibetans in exile to be hosted at the State Department in sixty years.

US-China relations

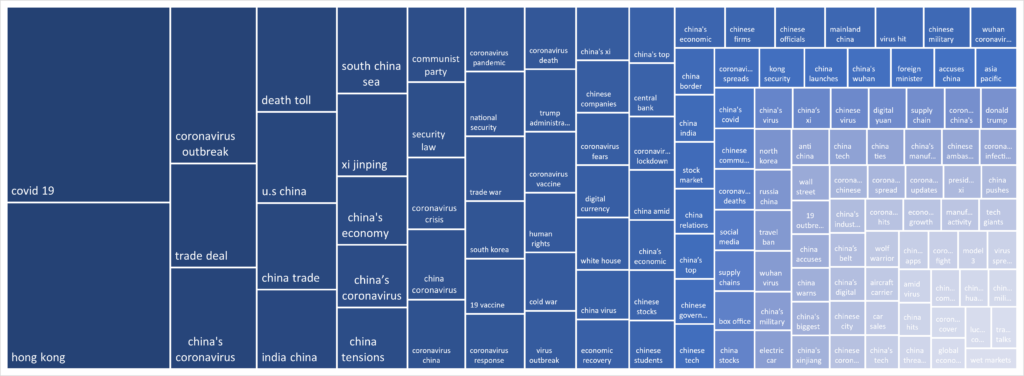

China is regularly the subject of intense rhetoric during American election years; this year, it was also subject to punitive action on multiple fronts. A trade agreement signed in January was soon overshadowed by a volley of actions intended to sanction Chinese behavior or reinforce demands for greater reciprocity. The coronavirus contributed to a sharp decline in American sentiment towards China. In January, the US blocked Chinese travelers from entering the country in an effort to prevent the spread of the virus; the collapse in international air routes left thousands, particularly Chinese students, in limbo and unable to return home. As part of his efforts to deflect blame for his administration’s mishandling of the virus, Trump repeatedly used the derogatory terms “China virus” and “Kung Flu.”

A State Department decision to cap foreign employees working in the US for Chinese state-run media outlets was followed by China expelling multiple journalists and stopping visa renewals for others, severely crippling many American news organizations’ operations. (Separately, Facebook and Twitter began to label posts by state-controlled media, including Chinese outlets.) In July, the US ordered the closure of China’s Houston consulate, which was soon followed by the reciprocal closure of America’s consulate in Chengdu. President Trump signed separate bipartisan laws permitting sanctions on Chinese officials responsible for violating Hongkonger and Uyghur rights. Military freedom of navigation operations were paired with a State Department announcement that China’s claims in the South China Sea were “unlawful,” which was echoed by Australia. Mirroring China’s restrictions on diplomats in its country, the US required Chinese diplomats to receive permission before visiting university campuses, meeting local government officials, or hosting large cultural events. Self-defeatingly, the US withdrew from the WHO to protest its alleged capture by China and ended Fulbright and Peace Corps programs in the country. The administration barred members of the Communist party from being eligible for permanent residency or citizenship; it reportedly considered a travel ban on all Communist Party members which was ultimately diluted.

The United States also continued to aggressively pressure some of China’s technology giants. The country’s campaign against Huawei gained support in the United Kingdom and less definitively in Germany. TikTok was forced under the threat of an outright ban into an agreement intended to protect American users’ data from exploitation by Beijing. (A ban on WeChat has been temporarily blocked by a federal judge.) The US also imposed export controls on SMIC, a major semiconductor manufacturer. In a series of speeches, American officials warned of China’s multifaceted challenge to the country and the free world; corporations and state and local governments were told not to be co-opted by China, while universities were subject to investigations of their ties to China and tightening visa restrictions.

International affairs

The combination of the coronavirus, Hong Kong’s national security law, repression in Xinjiang, and provocation of territorial conflicts from the Himalayas to the South China Sea hardened much of the world against China. China’s attempts to turn the coronavirus to its advantage via “mask diplomacy” backfired, due to China’s perceived haughtiness, the poor quality of some of the medical and protective equipment offered, and a parallel misinformation campaign intended to deflect blame over the pandemic.

The violation of Hong Kong’s autonomy alienated many countries and prompted some of the most overt criticism and forceful responses since Tiananmen Square; numerous countries suspended extradition treaties with the territory and extended paths to residency and citizenship to Hongkongers seeking to leave. At the United Nations Human Rights Council a declaration supporting Beijing won the support of 53 nations, while a declaration expressing concern secured 27 votes, a sign of Beijing’s sway in global institutions.

Europe, which last year declared China a “systemic rival,” appeared to reach an “inflection point” in its relationship with China, despite late agreement of an investment treaty. Charles Michel, President of the European Council, said before the United Nations that the continent is “deeply connected with the United States. We share ideals, values, and a mutual affection that have been strengthened through the trials of history … We do not share the values on which the political and economic system in China is based.” A trip to Europe by China’s foreign minister in an attempt to reset relations was “decidedly chilly.” The hardening of Germany’s political and business establishment was particularly notable – with the exception of the country’s chancellor, Angela Merkel, who is in her final term. The country’s business community increasingly sees China not as a customer, but as a competitive threat. The United Kingdom’s “golden era” with China reached a similar state of disillusionment.

Indian and Chinese soldiers clashed over disputed territory, resulting in multiple casualties. India retaliated asymmetrically by blocking many Chinese apps and signaling a willingness to both further align itself with Washington and challenge China’s vulnerable maritime supply chains. Relations with Japan and South Korea were stable: a planned visit by Xi Jinping to Japan was delayed due to the coronavirus; Japan’s new prime minister did not appear likely to augur major shifts.

China’s hostage diplomacy of Canadian citizens continued as Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou’s awaited extradition to the United States. Australia made clear that its sovereignty would not be bought or coerced away. New Zealand, whose perceived pull into China’s orbit had prompted warnings about its future in the Five Eyes intelligence alliance, quietly but clearly set a new trajectory for its relations.

African diplomats registered rare protest against China’s government for discrimination against Africans in China during the coronavirus outbreak. In Latin America, the US and China competed to provide aid to a region which was heavily impacted by the pandemic.

The Middle East was a rare source of diplomatic gains. Iran, embittered by US abandonment of a nuclear accord reached under the Obama administration, pursued closer ties with Beijing. Beijing reportedly helped Saudi Arabia construct a facility that would advance its nuclear program. The country also aimed to deepen its presence in Afghanistan, offering to build a road network for the Taliban in exchange for peace after the US military leaves.

Economy and business

China recorded its first quarterly decline in GDP for the first time in four decades in the immediate aftermath of the coronavirus; for the year, however, it was expected to record a modest gain of 1.9 percent, outperforming every other major economy, and allowing the country to declare it had met its target of eradicating extreme rural poverty. New research showed a dramatic curtailment of China’s overseas lending.

The country’s abandonment of GDP targets was by no means an indication the economy would be any less state-led: the Communist Party affirmed private companies’ obligations to commit to “United Front Work” that advances Party objectives, a move which will likely invite further suspicion upon Chinese companies operating abroad. Speaking virtually to the United Nations, Xi pledged that China’s economy would become carbon neutral before 2060. The country announced that by 2035, all new cars sold would be at least hybrids.

The coronavirus accelerated reconsiderations of corporate and national supply chain exposure to China. China too embarked on a “dual circulation” strategy to lessen its foreign exposure, even as it signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a major trade agreement. The country’s modest growth for the year showed a continued reliance on debt, excess property investment, and state-owned enterprises. Baoshang Bank, which Beijing seized last year, was allowed to enter bankruptcy, the first by a commercial bank in two decades; Evergrande, China’s debt-laden developer, avoided a similar fate. In Shenzhen, China’s first personal bankruptcy law was drafted as delinquent loans soared.

The initial public offering for Ant, the financial spinoff of Alibaba, poised to have been the world’s largest ever, was suspended in a rebuke of founder Jack Ma. America’s and China’s financial system came closer in some respects even as they came apart in others. Multiple Chinese companies listed on American stock exchanges did secondary offerings in China or delisted entirely to limit the risk they would be targeted by the US government. (Late in the year, a White House executive order barred Americans from investing in stocks tied to China’s military and Congress passed legislation that would ban Chinese firms from American stock exchanges if they failed to comply with audit standards.) Wall Street, however, intensified its exposure as China granted a host of approvals or otherwise relaxed regulations, including allowing Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanely to take majority control of their Chinese securities subsidiaries. Beijing sold dollar debt directly to US investors for the first time while the valuation of China’s domestically listed companies reached record levels. Short-sellers exposed Luckin Coffee’s fraudulent accounting practices. Alibaba sold a record $75.1 billion in goods during this year’s Singles Day.

Society and culture

Births in the prior year reached lows not experienced since 1961 as China’s demographic challenges accelerated. Intense flooding killed hundreds and displaced millions. China adopted its first civil code, which principally consolidated existing law. The Vatican and Beijing renewed their power-sharing agreement on the appointment of bishops. In science, the country completed its Beidou satellite network, an alternative to GPS; claimed an “important breakthrough” with a secretive space plane; and successfully retrieved lunar rock and soil samples.

The Eight Hundred, a war epic, was the world’s highest-grossing movie, as the coronavirus kept most other countries’ theaters closed and major Hollywood releases delayed. Disney’s Mulan, denied a theatrical release in most markets due to the coronavirus, earned lackluster reviews and controversy for filming in Xinjiang. Zoom, which became the essential videoconferencing service of millions during coronavirus lockdowns, was criticized for censoring talks on Tiananmen and Hong Kong protests held on its platform; it promised to change its policies.

A diary of life under lockdown in Wuhan inspired a global readership and mixed opinions in China on whether the author was a “voice of the people” or “traitor.” Notable books included an apologia for China by a former Singapore diplomat; a real-time history of the “new Cold War”; and a history of two Jewish families who shaped pre-Revolution Shanghai. An online magazine on China published by David Barboza, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on former premier Wen Jiabao’s family wealth, was launched.

Anson Chan, the highest ranking Chinese leader in British Hong Kong and a principled defender of the territory and its people under mainland rule, retired from public life. Lee Teng-hui, Taiwan’s first democratically elected president, died at 97. Stanley Ho, Macau’s casino mogul, died at 98. Li Zhensheng, a photographer who captured the Cultural Revolution, died at 79. Cecilia Chiang, restaurateur who elevated Chinese food in America, died at 100. Ezra Vogel, scholar of Japan and China, and author of a biography of Deng Xiaoping, died at 90.

=

In the year ahead, China’s diplomats’ failure to acknowledge the country’s role in the simultaneous deterioration of relations with nearly every major country – instead blaming others for “biases” and “strategic miscalculation” – suggest further worsening is more likely than rapprochement. The election of Joseph Biden as America’s next president will see tactics replace theatrics in the two countries’ confrontation, but to similar ends. The coronavirus will enter a new phase, as vaccine diplomacy replaces mask diplomacy.

China’s domestic prospects are no better as Xi’s consolidation of power continues. In her departing column as the Beijing bureau chief for the Washington Post, Anna Fifield closed with an observation, masquerading as a joke, expressed by some Chinese: “We used to think North Korea was our past – now we realize it’s our future.” Next year marks the one-hundredth anniversary of the CCP.

The words of Fang Fang, who authored the Wuhan Diary, are poised to transcend this year and China’s borders: “When the world of officialdom skips over the natural process of competition, it leads to disaster; empty talk about political correctness without seeking truth from facts also leads to disaster; prohibiting people from speaking the truth and the media from reporting the truth leads to disaster; and now we are tasting the fruits of these disasters, one by one.”

This article has been updated to reflect the EU-China investment treaty and the death of Ezra Vogel.