Review of China’s Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy by Peter Martin. Oxford, 2021.

Diplomacy, it has been said, is “the art of telling people to go to hell in such a way that they ask for directions.” China’s diplomats are considerate enough to share directions without waiting to be asked, having become notorious in recent years for their increasingly strident tone. The cause has less to do with China’s hubris, although it is certainly a factor, than it does with the insecurity of China’s diplomats in a political system that does not trust the world and, by extension, them.

Peter Martin, a reporter for Bloomberg, writes in his new history of the People’s Republic of China’s diplomats that this dynamic has been inherent from the very beginning. The book’s title comes from a still-invoked mission that China’s diplomats are to be “the People’s Liberation Army in civilian clothing.” That aspiration was literal: the PRC’s first diplomats as a new nation were senior PLA officers prized for their loyalty but who had little to no experience with foreigners, let alone command of languages or diplomacy.

China’s nationalism further inhibits its diplomats; Martin affirms that their regular invocation of the risk of angry masses misperceiving concession as weakness is as much truth as it is a negotiating tactic. The result, Martin writes, is a system that is effective at formulating demands and silencing critics, but poorly equipped to win hearts and minds, let alone set a constructive global agenda.

Martin intersperses major events in the Communist Party’s diplomatic and political history with character sketches of a number of key actors. None, of course, loomed larger than Zhou Enlai, who founded the ministry and whose instinct for self-preservation allowed him to ride out the many vicissitudes others faced under Mao. But few are engaging as Ke Hua, Xi Jinping’s ex-father-in-law, who, as ambassador to the United Kingdom from 1978-1983, as China began its reform and opening, sent frank cables back to Beijing challenging Marxist doctrine and encouraged his staff to “speak the truth” or, at least, “fewer falsehoods.”

China’s diplomacy has evolved over four distinct eras of survival, recognition, stability, and control. In the survival era, its fate was contingent upon Soviet support and American ambivalence about the Nationalists. In the recognition era, notable successes included the Bandung conference of developing countries, replacing the Republic of China in the United Nations, and detente with America. In the stability era, its signature successes included the return of Hong Kong and Macau, entry into the World Trade Organization and the Olympics. Under Xi, the CCP seeks to entrench its neomercantilist model; draw on global sources to renew its domestic legitimacy; counter foreign opposition to its ambitions; and decouple from foreign sources of influence, leverage, or vulnerability it cannot control.

To be clear, Martin’s history is far from a comprehensive assessment of China’s foreign policy, let alone its foreign policy actors. Understanding China’s objectives, the roles of the party and military, and even key details about the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ diplomats themselves are underexplored.

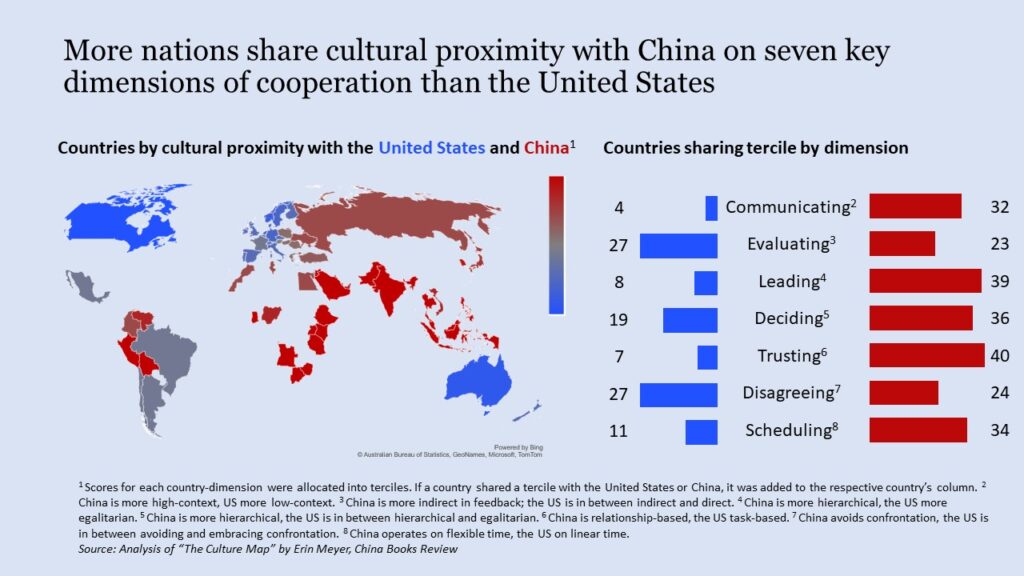

It is not only China’s political system and institutional dynamics that hinder China’s diplomats. Indeed, China’s diplomatic shortcomings are all the more stark relative to all that should attract much of the world to it. Its economic success understandably resonates with the developing and post-colonial world, especially in light of its own semi-colonial history; its political system is in accord with resurging authoritarianism; and possesses a compelling cultural heritage. By one measure of similarity in how nations build trust and make decisions, China is closer to far more countries than the United States (see graphic).

And yet, broad-based diplomatic success eludes China. More than seven decades since the founding of the PRC, its foreign policy remains decidedly mixed: it has survived and to some extent prospered, but with no true allies, many wary neighbors, an increasingly skeptical global public, and a Taiwan that is still beyond its grasp.

What ultimately holds China back is a still persistent internalized belief in its civilizational superiority and implicit rejection of Westphalian notions of equality among nations. Yang Jiechi’s infamously telling remark “that China is a big country and other countries are small countries” is not an exception, but a reflection of deeper ideological undercurrents. (Howard French’s Everything Under the Heavens is one of the best examinations of this ideological history.) China’s homogeneity and Han nationalism conspire to form a nation that struggles to understand the viewpoints of others, the foundation of successful diplomacy. It is especially for this reason that one wishes that Martin spent more time examining the influence of China’s few women and ethnic minority diplomats, including Fu Ying, an ethnic Mongol who remains one of the country’s most prominent spokespersons.

In focusing on the foreign ministry, Martin commits the same act of “mirror imaging,” imposing the dynamics of one’s own system on the analysis of another, that China’s diplomats frequently commit themselves. In China’s party-state, the ministry is the frontman of a show it has limited control over; indeed, Martin highlights multiple instances in which the country’s diplomats were credibly caught unaware of actions taken by other parts of its government or expressed their own private disagreement. More attention ought to have been given to the party’s Central Foreign Affairs Commission, which supersedes the ministry. And apart from characterizing China’s bureaucracy as “stovepiped,” Martin largely ignores the role of China’s military in shaping its foreign policy and its own extensive diplomatic apparatus. With respect to economic diplomacy, he misses an opportunity to point out the fundamental incoherence of the Belt and Road Initiative and the West’s consistent overestimation of China’s strategic capabilities.

While Martin states that China’s diplomats have come a long way in their training and area and subject knowledge, he provides no detailed judgment in this regard. Two proxies are the quality of China’s academic output on foreign affairs and the institutions that serve as the primary feeders to its diplomatic corps. Despite having the second largest number of the world’s think tanks, only three rank in the top fifty, according to an index compiled at the University of Pennsylvania, versus 14 for the United States. As for talent, Beijing Foreign Studies University, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ primary feeder school, ranks among the world’s 800-1000 best universities, according to the QS ranking; by contrast, six of the American foreign service’s top ten feeder schools have a rank of 250 or above.

As China becomes more powerful, its structural inability to operate an effective diplomacy makes it, in some ways, ironically less influential. An argument could be made that China’s diplomats should be seen not as constrained and insecure – though they are – but instead useful agents that distract and obstruct the rest of the world’s diplomats while China pursues its objectives by other means. For all their rote talking points, China’s diplomats are strikingly effective at seeding the global discourse with false dichotomies, particularly invocations against a new cold war or allegations that legitimate criticism is racist. Martin appropriately recognizes concerns about China’s united front tactics of co-opting foreign actors, but offers too little about China’s increasing efforts to steer international organizations in its favor.

How should other nations respond to China’s counterproductive diplomacy? The United States ought to consider sidestepping the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and instead demand more direct engagement with the Party. China’s rebuff of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin’s request to meet with the vice-chair of the Central Military Commission, who outranks the defense minister, should be taken as an invitation to other allies to demand the same across all areas of government. It is both a recognition of who holds power in China’s system and a rebuke of Xi Jinping’s evisceration of the party-state divide. Meanwhile, social media companies should go beyond their current labeling of government affiliated accounts and restrictions on promoted posts. One approach would be to prevent their posts from going viral by requiring one to visit their profile (as opposed to having them appear on one’s timeline). This could discourage some of the incentives for vitriol while still permitting China’s diplomats access to a public forum they deny their own people.

China’s diplomacy has previously recovered from domestic-driven setbacks, most notably the Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen. Now with more diplomatic missions than any nation, China will doubtlessly overcome its current wolf warrior phase too. But the world that China’s post-wolf warrior diplomats emerge into is very much in play. The Communist Party is not engaged in an ideological competition in the sense that it seeks to export its contradiction-ridden model. Instead, it seeks to diminish the threat it perceives liberal societies present to its hold on power. Free societies must hold fast.