Review of Mahjong: A Chinese Game and the Making of Modern American Culture, by Annelise Heinz. Oxford, 2021.

There are many ways to ingratiate oneself in China. In many settings, passable Mandarin, an appreciation for Chinese cuisine, or tolerance for baijiu will suffice. In your correspondent’s experience, there has been no surer bridge than an ability to play mahjong. But for many Americans, the game commands a devoted following among those with only the most tangential or no connection to China at all. In her new book, Mahjong: A Chinese Game and the Making of Modern American Culture, Annelise Heinz presents a fascinating history of a game that is less a source of cross-cultural connection than it is a complex reflection of American cultural transmutation and racial, gender, and consumer ideologies at work.

Mahjong is won by assembling combinations of sets of tiles. While the game can be played “along a spectrum of competitiveness,” it rewards those with a situational awareness of the tiles and their competitors’ hands. Originating in mid- to late-1800s Chinese gambling dens, mahjong’s 1920s arrival in the United States was comparatively swift, facilitated by American expats. (Even today, the misperception – encouraged by early marketing – reigns that the game is ancient.) Joseph Babcock, a Standard Oil executive based in China, took a leading role in marketing mahjong, before growing frustrated at his failure to monopolize it and selling his interest to Parker Brothers. But for every Babcock, Heinz emphasizes, women were far more influential in the game’s spread from Shanghai expat circles to high and middle class society back home.

In America, mahjong’s reception was about more than a game. It was a window onto a changing consumer culture and gender norms, and represented a more troubling continuation of America’s tendency to ‘commodify and denigrate’ non-white cultures. Heinz, an assistant professor of history at the University Oregon, deploys a remarkable assemblage of cultural artefacts of mahjong’s broader cultural resonance.

Mahjong earned a distinction as one of the first trends to spread from West Coast to East and independently from Europe, connecting “novel forms of production, distribution, and marketing with established markets for ‘Oriental’ goods.” By 1923, the game was China’s sixth largest export to the United States; in an ironic inversion of modern perceptions of bilateral trade, the mahjong boom sparked a flurry of cheap American imitators competing against more expensive, artisanal Chinese production. Competing manufacturers’ proliferation of “contradictory” rules in an attempt to avoid trademark infringement may have been one cause of the game’s unsustained growth.

Mahjong’s association with gender was almost immediate. At its most faddish, American women embraced mahjong as a pretext for experimentation, hosting games dressed in Chinese costume as both a manifestation of the 1920’s new sexual permissiveness and an already pervasive exoticization of Asian women. (A New York Times essay christened a Chinese American flapper as “Miss Mah Jong,” writing that in embodying “the East and the West in one,” she was “so eternally exotic.”) On its way to taking up residence in the suburbs, mahjong would be scapegoated more than once as the cause of disrupted home lives.

Mahjong also exemplified America’s schizophrenic approach to race, veering wildly between respectful adoption and assimilation to outright misappropriation. As the game first spread in popularity, commentators were quick to remark in racialized undertones that it was poised to overtake bridge. Whereas today the Chinese game go is the preferred cliché for explaining China’s strategic ambitions, mahjong’s addictiveness was then invoked to explain why the Chinese had “never built a powerful nation.”

While some Chinese Americans – many of whom were introduced to the game at the same time as the rest of the country – sought to leverage the game as a point of mainstream connection, they were generally rebuffed. In popular culture, while white men could be portrayed as seduced by a Chinese American woman over a game of mahjong to humorous effect, the game was portrayed as a threatening pretext in regards to Chinese American men and white women. Consequently, white women were preferred as in-home instructors, with Chinese Americans hired as in-store markers of authenticity, in some instances literally situated in storefront windows.

After its initial nationwide craze, mahjong would assume a quieter, but more enduring foothold among Jewish American women, who founded the National Mah Jongg League to promote a standardized version of the game. Heinz details how the game became a vital source of connection and marker of Jewish identity as second-generation Jewish American women moved to the suburbs. The game remained a symbol for discussing women’s roles; often the game was used for philanthropic purposes so that well-deserved leisure could be ‘legitimized’ as productive.

In China, the game’s initial American popularity heightened its prestige, to the dismay of missionaries and reformists alike. While the Communist Party once banned mahjong – and continues to discourage it among officials – today, China’s parks host no shortage of games, just as it is common to see chess players permanently stationed in New York’s parks. (To the envy of some American mahjong players, Chinese households commonly boast tables that automatically reset the tiles.) As ever, the stakes can range from bragging rights to considerable sums.

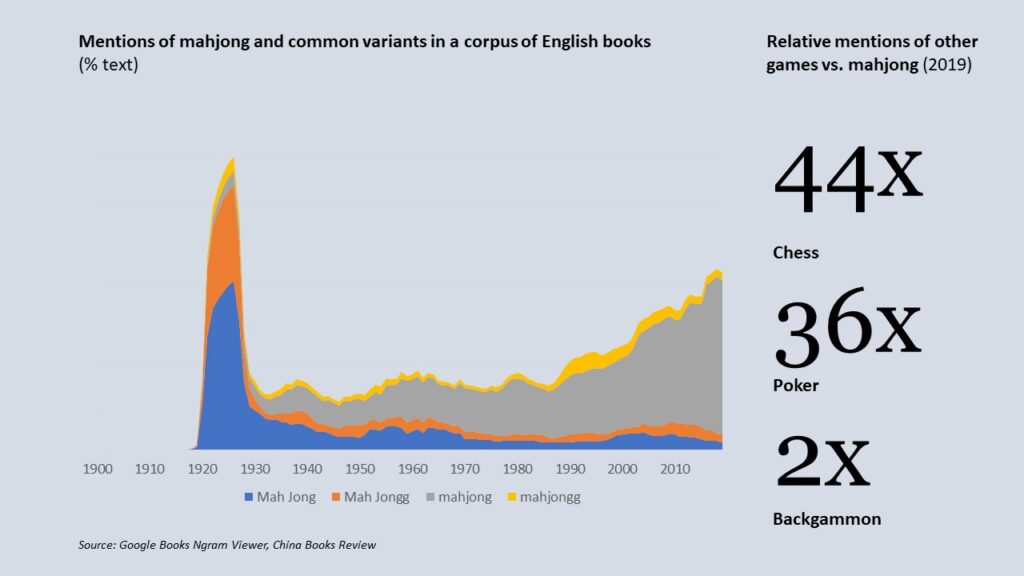

Mahjong continues to make regular cameos in the American popular imagination, from Philip Roth novels to Amy Tan’s Joy Luck Club and, more recently, Crazy, Rich Asians and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. Today, Facebook identifies nearly 1 million Americans with an expressed interest, among them retiring baby boomers taking up their mothers’ game. Mentions of the game in a corpus of books tracked by Google show the game approaching 1920s levels of salience, even as it was and continues to be dwarfed by games like chess. None of the top sets on Amazon are among the top ten thousand most popular products in the toys and games category.

While Heinz concludes with signs of mahjong’s belated adoption for genuine cross-cultural connection, the game’s early history is a timely and unexpected cause for reflection amid a surge of reports of violence directed towards Asian Americans and heightened mistrust of China. Mahjong’s history is a reminder that the extent to which Americans can alienate their own is neither new nor particularly less pronounced. In demonstrating America’s capacity to willfully misinterpret China, often by those who should most know better, mahjong’s arrival in America illustrates a still too pervasive tendency towards oversimplification of that country, with increasingly grave consequences.

And yet, for all the semantic burdens mahjong may carry, it remains a delightful game which Heinz’s engaging prose fully captures. She reminds us that “mahjong is a game of the senses. The tiles hold beauty … heavy in the hand, … thumbs bump against grooves in the tiles from impossibly intricate carvings or brightly colored embossed images. Nothing else mimics the clang of mahjong tiles running over each other on a hard table; even a felt top does not entirely soften the din. Regardless of when and where the game is played, these experiences remain.”