Review of Where Great Powers Meet: America and China in Southeast Asia by David Shambaugh. Oxford, 2020.

Southeast Asia is framed as the front line of America and China’s global competition. That is, to some degree, self-serving for the region, whose countries seek to balance China’s economic opportunities with American security guarantees. But why this dynamic must be framed as a competition at all, for reasons other than for the sake of competition itself, is an elusive subject in a new survey of the region.

The ten nations of Southeast Asia, which collectively possess a population of more than 600 million and an economy comparable to France, are highly diverse, encompassing archipelagos and a city-state, the very rich and very poor, secular states as well as the world’s largest Muslim nation. Geographically, Southeast Asia bestrides a crucial choke point in global trade. Considerable naval resources have been devoted to ensuring freedom of navigation and preventing the denial of access should conflict arise; China has also invested aggressively in infrastructure in the region that allow it to bypass the strait.

It would be one thing if American and Chinese competition were limited to the sea; but it extends well inland, taking on a wide array of economic and diplomatic dimensions whose rationale, at least for the United States, merits scrutiny. For Beijing, the desire to assure the stability of its immediate region is clear and the region’s economic potential an added bonus. But for the United States, which does not share China’s mercantilist outlook, and which could conceivably achieve its strategic objectives with a far narrower commitment of resources, why need this be a competition at all?

It is perhaps this uncertainty that explains why, if America’s engagement in the region were reduced to a single word, “inconsistent” would be a fair assessment. America shows up most forcefully when it wants a means of pushing back against China and steps back when the country is not the subject of its foreign policy animus; any inherent value the region possesses is thus secondary. As the American and Chinese contest for global leadership intensifies, the former should weigh carefully whether defaulting to Southeast Asia as the foremost field of competition is the most productive use of its strategic capital, asking whether the competition for influence there is a fight that the United States can and must win.

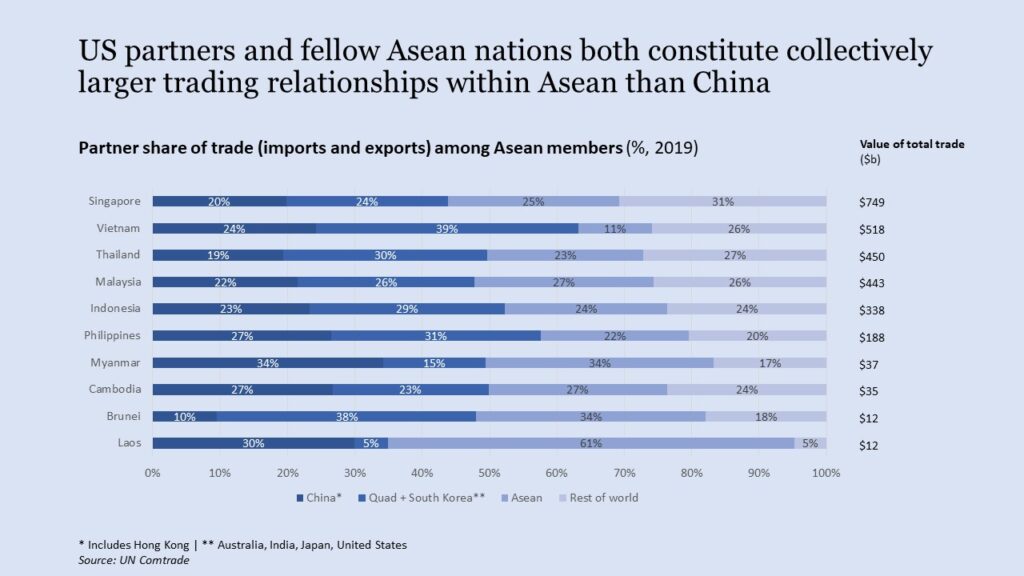

Instead of interrogating the continued centrality of Southeast Asia to US-China competition, David Shambaugh, a leading authority on China’s international relations based at George Washington University, presupposes it. And while attentive to the perspectives and interests of Southeast Asian nations, individually and collectively via Asean, the book’s narrow focus on America and China ignores a broader array of influences that, on net, favor the United States. Consider bilateral trade, which is one benchmark for influence. Head-to-head, China is the larger trading partner of all ten Asean nations compared to America. But America is not alone in the region: when Japan, Korea, and other regional leaders that share its values are consolidated, they eclipse China in seven of the ten countries. Collectively, the value of trade with Asean nations themselves eclipses China for six of the group’s constituent countries.

Shambaugh’s recommendation that the United States more consistently show up and step up so that Southeast Asian countries may better balance against China ought to instead be recast as a recommendation to better coordinate among its partners and elevate Asean’s own collective autonomy.

The incoming Biden administration will have a number of opportunities to do so once it assumes office. The first is to recommit itself to the Transpacific Partnership. Second, America’s underfunded mission to Asean deserves more resources and the authority to coordinate the efforts of its sister embassies. Third, is to leverage the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, in collaboration with South Korea, to establish a more unified Asean engagement strategy on both security and economic matters.

The United States’ paltry public diplomacy and human capital investments – Shambaugh reports the US spent only $52 million across the entire region on public diplomacy in 2017 – also merit greater support. Shambaugh spotlights a number of underappreciated assets, including the Department of Defense-run Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, whose programming has reached scores of current and eventual ministers, ambassadors, flag officers, and several presidents and prime ministers. Moreover, in a region whose leaders are often reluctant to publicly recognize its partnerships with Washington, the United States can do more to let Southeast Asia’s people know of its already considerable commitment.

China, which is seen in the region as increasingly overbearing, has, in Shambaugh’s assessment, nonetheless brought seven of the region’s countries into more consistent alignment with its interests than that of the United States. Among them, Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar are most closely captive to Beijing, while Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, and Thailand occupy a more ambivalent posture that has trended in its direction.

Shambaugh downplays the Philippines’ break with the United States under Rodrigo Duterte. He suggests that Duterte’s personal animus towards the United States has at most guided the country into the same posture of studied ambivalence of most Asean states. Nonetheless, Duterte’s attempts to elicit Beijing’s largesse has brought little tangible gain. Surprisingly, Shambaugh assesses Vietnam as even more aligned with US interests than Singapore, despite far greater overlap in worldview and economic and defense ties with the latter.

It is Thailand which Shambaugh characterizes as the most important “swing state” in the region, principally given its strategic location. Its ‘loss’ to China, he writes, would be a “devastating blow to America’s strategic position.” The country’s drift towards Beijing has accelerated in part because the country’s most recent coup in 2014 has obliged Washington to keep its distance. As this year’s unprecedented youth-led protests against the country’s monarchy continue, the Biden administration will have an opportunity to reassert American influence and test renewed cooperation with Germany, where the Thai monarch spends most of his time.

As an academic based in Washington, Shambaugh is clearly comfortable navigating officialdom, and on a number of his visits to embassies and ministries throughout the region he prompts strikingly frank comments from his interlocutors. Nonetheless, the book would have benefited from engagement with a broader set of actors, including opposition lawmakers and civil society and business leaders. Shambaugh expresses disappointment that the region’s academic understanding of China – as well as China’s understanding of Southeast Asia – is woefully limited, but never fully develops its implications or the opportunity for the United States to play a role. A brief examination of Washington and Beijing’s actions and rhetoric towards Latin America, and how that dynamic compares with Southeast Asia, would have also been illuminating.

Among the various scenarios Shambaugh envisions for the region, his “good news” outcome would be continued “competitive coexistence.” In this scenario, Washington and Beijing seek to advance their interests without directly countering the other in zero-sum competition. That would be wise. It is possible for the United States to protect its and its allies’ interests and support the strategic autonomy of non-aligned nations without engaging in a more costly competition for dominance. If the United States can strike that balance in Southeast Asia, it bodes well for America’s ability to manage China’s far from inevitable rise elsewhere too.