In 2023, China continued its inward turn as optimism for a post-Covid recovery, both economic and spiritual, ceded to malaise. The Communist Party no longer espoused prosperity, or even its own competence, but instead trafficked in insecurity. Xi Jinping warned of the need to prepare for “worst case scenarios” and the Ministry of State Security called for the “mobilization of all members of society” against espionage.

The apparent triumph of the national security state gives license for the subordination of rational policy to its dark imperatives. China’s own modern history demonstrates how systemic insecurity feeds upon itself; how overwatch devolves into misgovernment; distrust into disorder; and economic frictions into decay.

In the year ahead, the peat fire pervading China’s financial system will especially challenge the country’s shadow banks, which combined with multiple de facto local government bankruptcies, may cause widespread unrest. Diplomatically, China may benefit from countries, including close American allies, seeking to recalibrate their ties after a period of distancing. America’s election will be a contest between keepers of a global order towards which China is ever more hostile and agitators of chaos in which China has no greater certainty of success.

Continue reading “The year in China 2023”

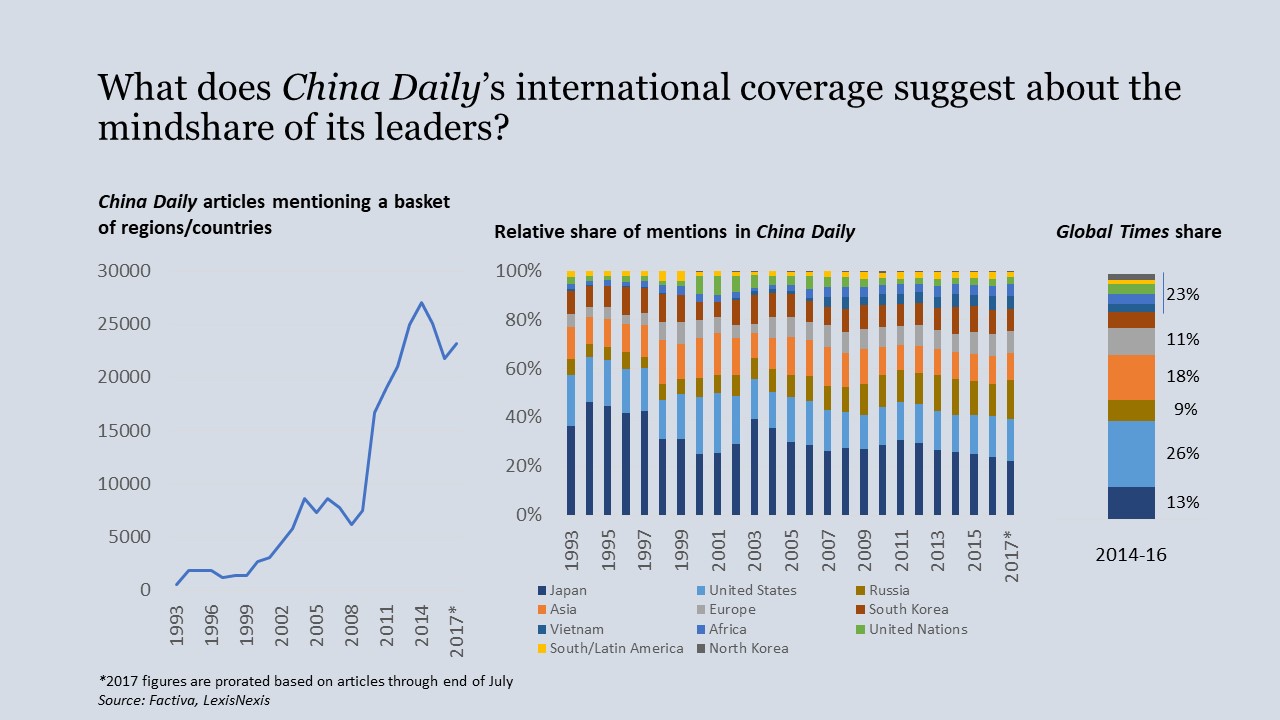

Reading the tea leaves in old-school Kremlin- or Sinology has often meant paying close attention to newspapers – what is said and what isn’t, who is mentioned and who isn’t. The approach may still have its uses for understanding Chinese foreign affairs.

Reading the tea leaves in old-school Kremlin- or Sinology has often meant paying close attention to newspapers – what is said and what isn’t, who is mentioned and who isn’t. The approach may still have its uses for understanding Chinese foreign affairs.